The geopolitical landscape shifted dramatically over the past five years. America’s hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 followed by its deepening entanglement in the Ukraine war – now widely understood as a grinding proxy conflict between NATO and Russia – laid bare the limits of US power.

In the Middle East, Washington has struggled to rein in crises involving the Houthis, Iran and Syria, while continuing to underwrite Israel’s genocide in Gaza. In East Asia, its commitments are increasingly strained by a rising China and a more assertive North Korea. At home, inflation, border insecurity, and social fragmentation have all contributed to the growing sense that American primacy – both global and domestic – is faltering.

No country stands to be more affected by America’s relative decline than Japan. Since the end of World War II, Japan has remained tethered to Washington – militarily, politically, even psychologically. Its defense is largely outsourced; its politics, heavily influenced by American interests. Its media class repeats Washington talking points verbatim.

As Washington stumbles, the postwar establishment in Japan has stumbled, too, clearly unable to envision a world in which Washington is no longer supreme.

But that post-Washington world is coming quickly, and is in many ways has already arrived. If Japan is to prepare for the rapidly emerging multipolar world, it must begin a process of strategic decoupling from America. This does not mean a reckless severance of ties overnight, but a clear-eyed and deliberate effort to reassert autonomy in key areas of diplomacy, military and economics.

First, Japan should consider initiating dialogues with leaders and entities typically seen as unaligned with the so-called Washington-led liberal international order. Such meetings would signal Japan’s intent to diversify its diplomatic options but also serve as pragmatic steps toward resolving longstanding regional challenges.

Japanese officials could, for instance, quietly open communication channels with North Korea. A key objective would be the resolution of the abductee issue – a humanitarian matter that has lingered unresolved for decades.

For far too long, pro-Washington elements within Japan’s conservative establishment have relied on the US to lead negotiations over the abductions. The issue has often been subsumed under broader strategic aims, such as the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula or curbing the North’s ballistic missile capabilities.

North Korea, however, has little incentive to cooperate under the current framework. North Korea understands that returning the abductees is tied to denuclearization, Washington’s priority, so the issue is stalemated.

Entrenched interests in Japan ensure that Tokyo and Pyongyang will never meet bilaterally, effectively devaluing the abductee issue by making it subordinate to Washington’s geopolitical prerogative. This treachery by the Japanese “conservative” political class only guarantees that the abductees will never come home and that Japan will never pursue an independent course in East Asia.

A direct, Japan-led initiative – reminiscent of former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s approach – could help reenergize dialogue, not only on the abductee issue but also on the broader question of normalizing bilateral relations. If Japan were to reach out to North Korea directly, without acting as Washington’s cupbearer or message-bringer, then North Korea might respond more favorably to such overtures.

Second, Japan should re-engage with Russia, despite the current geopolitical tensions. Quiet, pragmatic diplomacy with Moscow could serve several objectives: securing energy resources, mitigating economic fallout from sanctions, and more critically, reopening dialogue on the status of the Northern Territories.

While immediate resolution of territorial disputes may be unlikely, recognizing certain political realities, such as Russia’s control of Crimea and other regions in Ukraine, could serve as bargaining chips in negotiations that prioritize Japan’s national interest. Tokyo should not rush to violate sanctions, but rather assess carefully whether incremental divergence from Washington’s stance could yield strategic benefits.

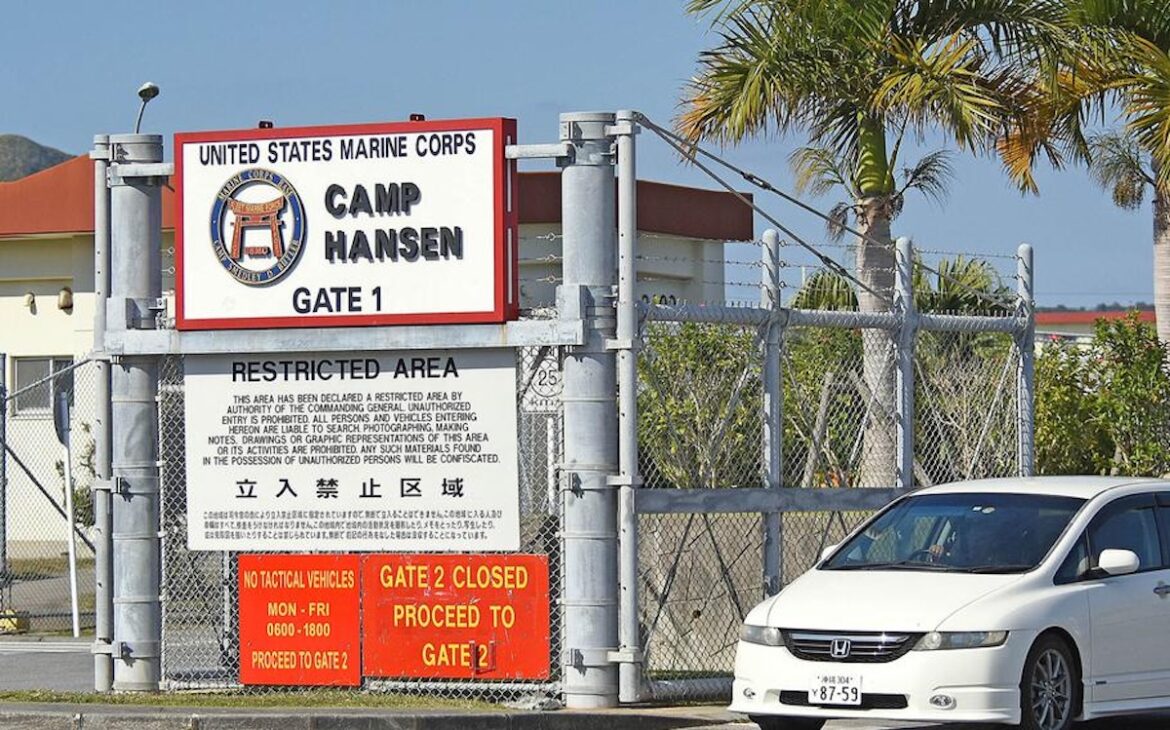

Third, Japan must begin to reassess the long-term presence of US military bases on its soil. While the alliance with the US remains foundational to Japan’s security framework in the minds of defense planners in Tokyo, a more autonomous defense posture should be part of a broader defense strategy.

“Double containment” is a phrase that Japan’s pro-Washington establishment needs to learn post haste. Japan could start by increasing its operational control and logistical oversight of select bases under the pretext of burden-sharing.

Over time, a phased and transparent renegotiation of the base structure could lay the groundwork for greater sovereignty in defense affairs, without triggering unnecessary confrontation.

In parallel, Tokyo should also begin a national conversation on revisiting the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. But it must be kept in mind that nuclear sharing is not a suitable long-term goal. Japan must work toward nuclear armament as a bedrock of Japanese sovereignty.

Fourth, Japan’s financial relationship with the United States, particularly its role as a major holder of US Treasury bonds, also warrants reevaluation. While an abrupt sell-off would be risky and self-damaging, a gradual diversification of Japan’s reserve assets and a reduction in exposure to US debt could serve as a long-term hedge against future volatility.

Bond markets are in turmoil and Japan is in very risky territory. More so given that the appetite in Washington for more debt appears insatiable. This is a losing proposition for creditor nations like Japan, so a reconfiguration is now an urgent task for Tokyo.

Fifth, any realignment of strategic posture must be accompanied by a national reckoning. Japan must hold a truth and reconciliation commission to bring to light the extent to which Japanese politicians, the Japanese media, and other people and institutions have collaborated with Washington during the postwar era.

Washington has not been Japan’s ally, but its overlord. Long after decolonization movements swept Asia, Africa, and Latin America, Tokyo has remained a slavish camp follower of Washington’s murderous foreign adventures. The Japanese people deserve to know exactly who has sold their country out to Washington as a first step toward taking Japan back from its colonial master.

Japan’s strategic decoupling from Washington will not be only a military, fiscal or political exercise. It must also be a time of soul searching, an opportunity to heal Japanese society by telling the truth about the past and allowing the Japanese people to digest the enormity of the crime their leaders have committed against them.

Co-author of The Comfort Women Hoax: A Fake Memoir, North Korean Spies, and Hit Squads in the Academic Swamp, Jason M. Morgan is an associate professor at Reitaku University in Kashiwa, Japan, an editorial writer for the Sankei Shimbun newspaper in Tokyo, a managing editor at the news and opinion site JAPAN Forward and a researcher at the Japan Forum for Strategic Studies in Tokyo, the Moralogy Foundation in Kashiwa, and the Historical Awareness Research Committee also in Kashiwa.

AloJapan.com