IN JAPAN, you are allowed to touch monks. Perhaps you already knew this. But I, who have for a dozen years lived in Thailand, where monks can’t have physical contact with women in case they have any lingering desires left unpurified, was extremely excited to learn this on my recent trip to Kyoto. Because there I met a monk—a top-level monk, the head of all the monks of the Nichiren sect—who I really wanted to hug. And I did, because Kojima-san, who is married with two daughters, is extremely huggable.

The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto (doubles from ¥190,000) introduced me to Kojima-san during what was ostensibly a food-focused visit, but in fact became friend-focused. Having forged strong personal bonds with fascinating fixtures of the community, the hotel is able to offer a perspective-altering collection of unique experiences exclusively to in-house guests. My days were filled with arts, spirituality, tracing the path from the ancient to the modern, biking the path along the Kamo River on which the plush, feng shui-forward hotel regally sits.

Showing off the day’s catch at Mizuki Sushi, in The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto

Showing off the day’s catch at Mizuki Sushi

Do pre-order the hotel’s Japanese breakfast

Oh yes, I ate exceedingly well on property: there is Mizuki, featuring a kaiseki, an omakase sushi counter and a tempura bar all in one beautifully convenient space—and where I suggest running while you can to get a glass of their 10th-anniversary sparkling sake; there is La Locanda, which does haute Italian with locavore ingredients (still dreaming about their burrata) for lunch and dinner, and a gift-box of a Japanese breakfast in the morning; and of course there is Chef’s Table by Katsuhito Inoue (prix fixe ¥35,000), an immersive, exclusive, bijou restaurant where you are plunged into the season, the smells and, at its best moments, the soul of Japan.

This is what I was here to find and so on my first morning I met Megumi Ebisu, destination manager at The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto, at the hotel entrance at 6:45 a.m. I’d say it was an ungodly hour, but we were heading to a temple. And I was glad that my first time biking in this city of cyclists was on empty streets. We pedalled along the pebbled paths of the Imperial Palace and as the sun started peeking through the trees we had the whole gardens to ourselves, which would have been a rarity later in the day and impossible during sakura or leaf-peeping seasons. We went through a New England-style university campus and down small alleys lined with wooden houses.

Myokakuji Temple

A gilded honour for a very generous donor

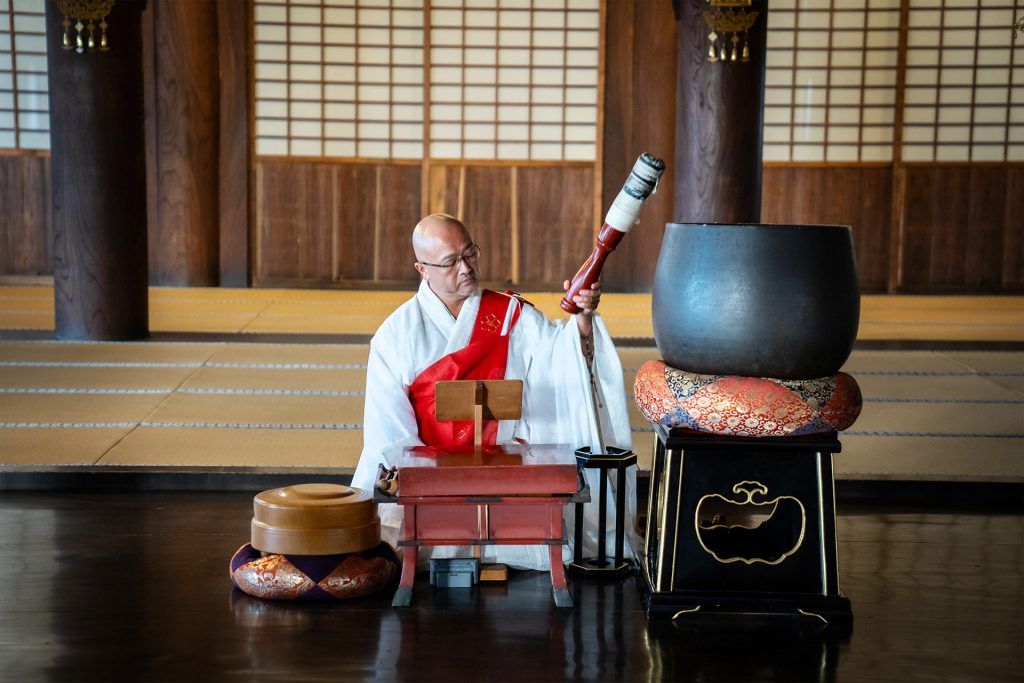

A bald man in frameless glasses, wearing a layer cake of pleated silk and gossamer white robes with an elaborate red sash over his left shoulder, greeted us at the entrance to Myokakuji Temple and led us through its grounds, a series of wooden buildings connected by covered wooden bridges. We came to a large hall filled with instruments cradled on silk cushions, the high ceiling a checkerboard of light and dark wood literally dripping in gold—including a gold plaque honouring a donor who had given the monastery US$8 million. Kojima-san gestured for me to sit on a small stool, and then he started chanting. A deep, guttural flow that reminded me of Mongolian throat singing. He moved around the room, from instrument to instrument, playing and chanting in a goodwill blessing for me. It was hard to believe a single man could conjure such a powerful sound, and for so long.

As we walked back along the covered bridges through the gardens where the first leaves were turning amber, Kojima-san stopped at a wooden board and hit it repeatedly with a mallet. This was a traditional “clock,” which the monks used to alert each other of the time. When he let me try, I lost count and wound up hitting it nine times for eight o’clock—but luckily I was able to redeem the reputation of my rhythm by playing the drums. Seated side by side on the floor on our heels, Kojima-san beat out a melody with his sticks and I followed along, until we were in sync. Then he sped up the pace to see if I could keep up. In a situation like this, it’s easy to see how mimicry is such a powerful bonding agent for babies and parents; by the end of the lesson, the ice was long broken and we were laughing like old friends.

Kojima-san is the head monk of Nichiren Buddhist sect

Learning to drum at Myokakuji Temple

Over tea, Kojima-san told me he’d once been a salary man, working his way up the ranks of a big Japanese conglomerate. Having joined their travel division, he arranged a trip for a monk, after which the master invited him to become his student. At the age of 28, Kojima-san embarked on a decade-long monk training, a requirement of which is a 100-day session in which the devotee lives in the woods and spends his days meditating and chanting, eating only soup only twice a day. It goes without saying this is an extremely severe and isolating way to test a person’s endurance. Kojima-san did it three times in 10 years, losing as much as 20 kilograms each time. I’m not sure I’d survive the PTSD of such an experience, but I suppose that’s the entire point. Today, Kojima-san is a convivial family man and avid golfer who, rather than running a firm, is big cheese of a Buddhist sect. An enthusiastic young man has approached him asking for mentorship, and in light of the dwindling population of Japan, he is considering training him to take over when he retires.

ANOTHER WAY to maintain traditions while looking to the future is clever adaptation. To understand this, Megumi took me to a place that crafts a symbol of Kyoto itself. Hiyoshiya, once the premier manufacturer of washi umbrellas—iconically carried by Maiko and Geiko, and displayed at temples and shrines—uses the same technique now to make table lamps and other collectible items. I spent an afternoon in their workshop, making my own lamp, and seeing how they craft umbrellas, propped up on large stands, the bamboo skeletons half exposed waiting for the rest of their washi paper coverings. A clay pot was filled with gelatinous tapioca glue, so thick that stirring it with a large pestle for just a few minutes would be a good substitute for arms day in the gym.

Honoka Suzuki at her Hiyoshiya workstation

Hiyoshiya, the premier maker of washi umbrellas (left) and a famous Hiyoshiya umbrella (right)

Throwing superstition to the wind, craftswoman Honoka Suzuki opened a stunning grass-green and white umbrella so large it could cover a picnic table—the sample from an order of several like it from a French company. One the size of a beach umbrella might take a month to complete, and Honoka-san, only in her twenties, told me that her favourite part of the work is what most might find most tedious: guiding the thinnest of threads through microscopic holes to hold the umbrella tines together. Clearly, even at this young age, even not a member of this historic family, she—like Kojima-san and perhaps his future apprentice—had what you might call a calling. It gave me hope for the future of dying arts.

It was a drizzly morning when Megumi and I pulled up at Kashogama pottery studio, on a nearly empty side-street not far from the tourist throngs of Higashiyama district. At the back of the room were four electric wheels, and I zeroed in on them so quickly I barely noticed the kaleidoscope of beautiful bowls, dishes, plates and cups all around me. I practiced pottery from age five to 18, and have done it sporadically as an adult, but it had been a long time since I had my hands in clay. Morioka-san, a fourth-generation potter with a degree from the same famed Kyoto arts school as Yayoi Kusama, offered up four different types of clay, and I picked a relatively soft gray one.

On the wheel in Kashogama studio (left) and a glazed bowl in Kashogama pottery studio (right)

On the wheel in Kashogama studio (left) and a glazed bowl in Kashogama pottery studio (right)

We wedged together—like kneading dough, to get the air bubbles out—and then took our places at wheels side by side. Throwing is about control, steadiness, being centred. Even with several people watching me, I had to make it a meditation, or I wouldn’t be able to make anything at all. Morioka-san helped me centre the mound of clay, gave guidance on thickness and height, offered a helping hand (or finger) every so often… but mostly I made the piece myself and when he realised I could, I basked in his astonished praise. Apparently, most people who come to Kashogama (by appointment only, note!) are beginners. And, yes, I am vain enough to be excited about beating non-present strangers at pottery.

When we deemed my bowl complete, Morioka-san led me back to the shelves at the front of the room, which, it turned out, were filled with not goodies for consumer purchase, but samples for student inspiration. The same colour glaze might look completely different not just combined with other colours but also alone on different clays. He sketched my bowl and we talked through how I wanted him to glaze it later before shipping it to me. (Such a great touch—and, it occured to me, reflecting the intersection of the Japanese spirit of helpfulness and The Ritz-Carlton’s of service. Most folks who book this experience are visitors, of course, and they don’t have weeks to wait in town for their pieces to be fired, glazed and fired again.)

Morioka-san discusses colour palettes

Morioka-san discusses colour palettes

I learned the white clay I had rejected, along with one of his reds, were native to Kyoto—making me regretful I hadn’t selected one of them. Morioka-san encouraged me to consider intention more, next time. What message or feeling I wanted to convey, then the type and size of object I wanted to make and how to glaze it, before even touching the wet clay. The problem for me on a wheel is having the power to control the shape rather than letting the shape control me. Perhaps that’s all of our problems, in some way.

BACK AT THE RITZ-CARLTON, Kyoto, just outside Chef’s Table by Katsuhito Inoue is a giant black-charred vessel that Morioka-san made in his enormous wood-fire kiln deep in the forest. He chops the wood himself and then keeps the fire going for seven days—at its peak, it hits 1,300 degrees Celsius for three nights during which he does not sleep. The uncontrollable flames, nature incarnate, are what give this piece its distinct beauty. And the same can be said of what you find inside the doors of this restaurant, as well.

Chef Katsuhito Inoue, right, plates dessert (left) and a delightful dinner party at Chef’s Table (right)

Chef Katsuhito Inoue, right, plates dessert (left) and a delightful dinner party at Chef’s Table (right)

The first thing you see is the living, daily changing centrepiece crafted by the hotel’s gardener, Kohki Suzuki. It’s a botanical garden on the table, artfully scattered with wood pieces, moss baubles, rocks, and seasonal leaves—reflective of the theme of this place, the 72 micro-seasons of Japan, for which chef, the son of a steakhouse owner and grandson of a wagyu retailer, holds great reverence.

Mushrooms foraged from the foothills of Mount Fuji. Tiger prawns still dancing on their skewers. Wagyu slices delicately shabued. Pasta made of red peppers and covered in fresh crab. Figs charcoal-grilled then hand-peeled. Three, tiny, perfect potatoes, mashed with a fork and divvied up among five. “The spirit of shimatsuno-kokoro [‘beginning to the end’] has been handed down from generation to generation in Kyoto. We should be grateful to nature and make use of all the ingredients carefully,” Katsuhito-san says. “Not only the expensive ingredients; fish bones, heads and organs are also necessary to use.”

Fresh figs grilled and peeled by chef Katsuhito himself (left) and wagyu tempura in Mizuki (right)

A dish covered in edible flowers at Chef’s Table by Katsuhito Inoue, in The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto

My dinner here was the ultimate culmination of all I’d learned in Kyoto. And not simply because the friends I’d made at each stop were so kind as to join me. (Have you ever had a wine pairing with a monk? You should.) But more because the restaurant, a temple to gastronomy and Mother Nature herself, demonstrates how we should keep the key lessons of our forebears—be they blood relations or not—and evolve them to meet the times. It also inspires and showcases reverence: for the lives given that we may eat, for the beauty in small things, for lyrical storytelling paired with plated minimalism, for the callings that define people and add such joy to our daily lives.

Kyoto is not necessarily the ancestral home to the best cuisine and crafts in Japan, Morioka-san explained to me, but it became their hub because the emperor’s court was here for centuries and the royals required the crème de la crème of the realm. “In Kyoto they collected all the best things,” he said, taking a bite of sea bream that chef Katsuhito had just assured us was the best in Japan. “I mean, for the ingredients, the food, the art and tradition, it’s all the same. They collected everything here together. And you know what? They created Kyoto.”

Cycling along the Kamo River, which The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto fronts.

Cycling along the Kamo River, which The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto fronts.

PHOTOGRAPHED BY CINDY BISSIG.

Article Sponsored by The Ritz-Carlton, Kyoto.

Written By

AloJapan.com